![]() Receive new posting via RSS feed. >Click the icon on the left to subscribe.

Receive new posting via RSS feed. >Click the icon on the left to subscribe.

(Or right click the icon to copy and paste the link into your rss reader)

Sleight of Brand

‘Sleight of brand’ is a form of slipstreaming that employs a variation of someone else’s brand to capture attention and intrigue. The play-on-words evokes but does not ‘pass off’ the new brand as being the famous brand.

‘Sleight of brand’ is a form of slipstreaming that employs a variation of someone else’s brand to capture attention and intrigue. The play-on-words evokes but does not ‘pass off’ the new brand as being the famous brand.

This month (May 09) in Australia, two companies called a truce in their legal skirmish over product copying. It began when cookie manufacturer, Arnott’s (owned by Campbell’s) objected to Krispy Kreme selling a doughnut called "Iced Dough-Vo” because it infringed on its own brand, the iconic Australian biscuit called ‘Iced Vo Vo’.

Krispy Kreme conceded that their product is designed around the same concept but "only to pay homage to what is a classic Australian product". That may sound a bit disingenuous but keep in mind that one is a cookie while the other is a doughnut. They are different products.

Krispy Kreme conceded that their product is designed around the same concept but "only to pay homage to what is a classic Australian product". That may sound a bit disingenuous but keep in mind that one is a cookie while the other is a doughnut. They are different products.

The intent here is not identity-theft. People know the two brands are different despite having the same rhyme and the same number of syllables and the same final syllable and both products being pink and edible. Why all the kerfuffle then and why does invoking a popular brand like this trigger so much media attention?

This is really a form of slipstreaming that I call ‘sleight of brand’. Just as entertainers do clever impersonations of famous people, so brands sometimes do light hearted ‘impersonations’ of famous brands. Just as Tina Fey mimicked the Sarah Palin character on Saturday Night Live, this type of brand impersonation act is strangely captivating. It is greeted with silent applause and if executed cleverly, generates lots of free media publicity - as happened here and probably to the benefit of both products.

Intrigue

To understand the power of ‘sleight of brand’ you have to realize that our brains find it captivating when something is uncannily like something else. Look at the next set of images. We immediately identify George Bush on the left and Arnie Schwarzenegger on the right. What is intriguing is the person in the middle. He fascinates because he reminds us of Bush or Arnie. Yet we are under no illusion that he is either one.

Reminding v Recognition

Our brain is well equipped to cope with mismatches. Even though this graphic may fire the pattern for Arnie or for Bush, it merely reminds us of them but doesn’t pass itself off as them. That’s because we have mismatch cells in our brain that fire in response to differences and match cells that fire in response to similarities.1 These are crucial because even when we see the same brand or the same person again, there is never a perfect match. (The lighting can be changed, the person may be older or have their hair shorter etc. Similarly, a familiar brand may now be in a larger pack with a redesigned logo or be formulated in a different color.)

Our brain is well equipped to cope with mismatches. Even though this graphic may fire the pattern for Arnie or for Bush, it merely reminds us of them but doesn’t pass itself off as them. That’s because we have mismatch cells in our brain that fire in response to differences and match cells that fire in response to similarities.1 These are crucial because even when we see the same brand or the same person again, there is never a perfect match. (The lighting can be changed, the person may be older or have their hair shorter etc. Similarly, a familiar brand may now be in a larger pack with a redesigned logo or be formulated in a different color.)

When a stored pattern fires along with enough mismatch cells, we do not interpret the experience as recognition; we do not see it as false identity. We interpret it as reminding. So Iced Dough-Vo reminds us of Iced Vo Vo by firing the Iced Vo Vo pattern in our brain. The difference with being reminded when the pattern fires, is that differences as well as similarities are salient.

‘Brand’ Examples

So just as the middle face captivates our curiosity, intrigue also occurs when we are reminded in a similar way of a famous brand. Here’s an illustration of a relatively unknown ‘brand’ identity invoking a famous ‘brand’ to help capture more attention.

In 2004, a candidate, running for political office in the city of Melbourne Australia used as his theme: “Raymond Collins for Lord Mayor. Everybody loves Raymond”. (Clearly, everybody did not love Raymond because he did not win. But that’s another story. He did get attention.

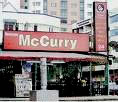

Another example of an unknown identity invoking a famous brand name is this. An Indian curry house in Malaysia called McCurry won an 8-year legal battle this month. The Malaysian court found that its use of the prefix ‘Mc’, does not infringe on the McDonald’s trademark. According to the court, there was no question of people confusing the two companies because McCurry offered completely different (Indian) dishes. In other words, McCurry invoked McDonalds … but it does not pretend to be McDonalds. Entertaining impersonations are to be distinguished from identity-theft.

By way of contrast in China right now, many counterfeit versions of the iPhone are being marketed (see NY Times story) that infringe patent as well as trademark rights because they are a direct copy right down to the keyboard, touch screen, the familiar Apple logo and the ‘iPhone’ name.

‘Impersonation’ through Word-play

‘Sleight of brand’ is when the unknown brand evokes, but does not pass itself off’ as the famous brand. Mostly it is a fun impersonation (or parody) of the famous brand and works a bit like a pun. People enjoy wordplay and they appreciate its cleverness. (See my column “A Pun is its Own ReWord”).2 And this liking response to the cleverness can wash over onto the brand.

For effective ‘sleight of brand’ to take place, the brand name doesn’t have to be identical and it doesn’t even have to be close, as long as by association, the word-play evokes the target in a reminding way.

I can think of some rock bands that have been particularly good at this. Think of the rock band “Howded Crouse’ who successfully slipstreamed the celebrity brand ‘Crowded House’. Also, think of the group ‘Bjorn Again’, a successful entertainment group that slipstreamed the ever-popular ABBA phenomenon (with no licensing fees to shell out).

Dickheads

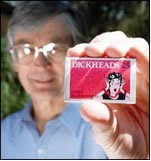

As a lovely illustration of ‘sleight of brand’ word-play, take this example. The Australian adventurer and businessman Dick Smith, back in 2000, launched his own brand of matches (for cigarettes). ‘Redheads’ is the traditional market leader and an iconic Australian brand. Dick Smith called his brand ‘Dickheads’ (sic!). Like Krispy Kreme, he conceded that he copied the concept but at the same time he was careful to also incorporate significant differences (as you can see from the pack shots).3 His intent was attention and intrigue rather than deception. Again, this is what distinguishes ‘sleight of brand’ from counterfeiting.

In the Dick Smith case, we see extremely clever wordplay because as well as copying the last syllable in the name Redheads, the first syllable is a clever play on Dick Smith’s own name. In a reminder fashion it evokes the famous brand but does not imply that the two products are identical… or even related. Yet at the same time, the consumer ‘gets it’.

Just as people appreciate cleverness in art, people appreciate cleverness in branding. A name like ‘Dickheads’ arrests attention in its own right and Dick Smith’s effort was doubly clever for the reason that it also exploited another source of attention - the taboo effect. (See my column The Swear**g Effect in Advertising).

Redheads waged a three-year legal battle against Dickheads but to no avail because, as with McDonalds in their fight against McCurry, they lost in the end…. and it is likely that Arnott’s Iced Vo Vo would lose too if they pursued their case.

Keeping Out of Court

Legal skirmishes are a hazard though because they can become prolonged. So, one way to minimize the legal hassles is not to target a competitor but instead perform ‘sleight of brand’ on a non-competitor.

For example, many companies have benefited by performing ‘sleight of brand’ on the famous retailer, Toys R Us. Think Wigs R Us, Dried Flowers R Us, Beds R Us, and even ‘Bibles R US’. Similarly many businesses perform ‘sleight of brand’ on the classic movie ‘Ghost Busters’. Think ‘Leafbusters’ (roof maintenance), ‘Bark Busters’ (dog training) and ‘Stain Busters’ (carpet cleaning).

For example, many companies have benefited by performing ‘sleight of brand’ on the famous retailer, Toys R Us. Think Wigs R Us, Dried Flowers R Us, Beds R Us, and even ‘Bibles R US’. Similarly many businesses perform ‘sleight of brand’ on the classic movie ‘Ghost Busters’. Think ‘Leafbusters’ (roof maintenance), ‘Bark Busters’ (dog training) and ‘Stain Busters’ (carpet cleaning).

Especially if you are not in the same business as the owner of the trademark, it makes it much less likely the company can sue successfully. Indeed, less likely they will sue at all.

The launch of the USA rock band ‘Postal Service’ is a final example to underline the potential advantages of ‘sleight of brand’. Instead of suing the band for co-opting its name, the U.S. Postal Service reacted by entering into a marketing agreement, inviting the band to play a concert for their senior execs and selling the band's CD through its website. USPS agreed to let the band keep using the name via this licensing deal and took advantage of its association through co-promotions.

Conclusion:

The free boost to marketing performance from ‘sleight of brand’ is no illusion. It can put the cream on the the Krispy and add power to the Postal Service. It is a magic method of slipstreaming and a wizard way to generate intrigue to capture both consumer and media attention.

Download pdf copy of "Sleight of Brand"

Notes:

1. Dolan, R. J., & Strange, B.A.,. Hippocampal Novelty Response Studied with Functional Neuroimaging. In Neuropsychology of Memory. Squire, Larry L. & Schacter, Daniel L., Guildford Press NY. 2002, 204-2142. Puns are dependent on a process known as frame-shifting, in which existing information is reorganized into a new frame extracted from long-term memory. See http://cogsci.ucsd.edu/~coulson/cogs179/coulson-severens.pdf

3. Sean Cowan, “Smith strikes a match winner in Dickheads dispute”. The Age. Melbourne. April 15, 2003