![]() Receive new posting via RSS feed. >Click the icon on the left to subscribe.

Receive new posting via RSS feed. >Click the icon on the left to subscribe.

(Or right click the icon to copy and paste the link into your rss reader)

Mind Bridges

When changing messages, construct a mind bridge between the old ad campaign and the new one so that consumers can use it to ‘cross over’ - from one to the other.

When an existing attribute (e.g. ‘the great taste of Pepsi’) is well established in mind, any change of message can face resistance and take considerable time to ‘wear-in’. That’s because the new one has to displace the old.1

However if you use a mind bridge, this doesn’t have to happen.

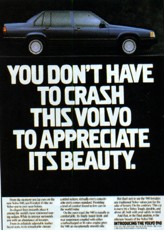

The trick is to enable something new to enter the mind without displacing the old. To do that, use a mind bridge. Here’s an example of a mind bridge. Years ago, when introducing the 940 model, Volvo wanted to focus on appearance instead of safety (the traditional Volvo attribute). Volvo did both by using this headline: ‘You don’t have to crash this Volvo to appreciate its beauty.”2

Note how this mind bridge reinforces the old attribute, (safety), while introducing the new (beauty), and enables both to be held in mind at the same time. In the absence of a bridge like this, the new is likely to be pitted against the old and they run the risk of interfering with each other.

As I pointed out in an earlier column (Information Intercourse), the human mind is like an interlocking structure. Ad campaigns along with brand attributes and things generally, ‘stick’ in the mind better when they integrate rather than are unrelated to each other. Integrating them means building a mind bridge – to help people cross from the old to the new.

Let’s look at another case example that underlines the crucial importance of a mind bridge - this one from my tracking experience.

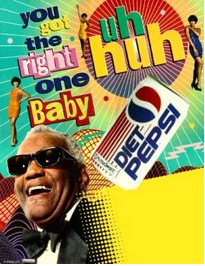

“You got the right one Baby…Uh, huh”

Pepsi’s platform for many years and the main focus of all its communications was taste. The peak of this was the Pepsi Challenge showing people preferring Pepsi to Coke. Then, in 1998 Pepsi launched the ‘Uh, huh’ Ray Charles campaign. This was quite catchy but it was a substantial departure from the previous single-minded focus on taste. The expression 'Uh, huh’ became a mnemonic that when we heard it, reminded us of Ray Charles and Pepsi. The full line was “You got the right one Baby…Uh, huh” - sometimes abbreviated to “Uh, Huh” .

Instead of going straight into the campaign, the following bridging commercial was use d at launch:

d at launch:

Ray Charles is playing piano and sipping occasionally from his can of Diet Pepsi near at hand. Several attractive girls try to trick him by switching it for a can of Diet Coke. Ray cannot see the switch (or indeed see the can) but he instantly detects the taste difference as soon as he takes a sip. He is highly amused at their joke. They return his can of Diet Pepsi and he tastes it approvingly and breaks into the launch catchphrase ‘‘You got the right one baby. Uh, huh’

It was a great bridging ad that not only introduced the ‘Uh, huh’ mnemonic but also linked it up in people’s minds with taste as the ‘reason why’ Pepsi was ‘the right one baby’. Thus, it enabled the ‘Uh, huh’ campaign to be seen as an extension and follow-on that reinforced the previous emphasis on taste. ‘Uh, huh’ was like a mnemonic for better taste.

The ads that aired following that bridging commercial made little reference specifically to taste.

See two of them here...

Although they made little reference to taste, nevertheless the ‘reason why’ it was ‘the right one baby’ had already been clearly established by that bridging commercial. The mind bridge played an absolutely crucial role.3

How do I know? Because that bridging ad failed to go to air in some regions (for reasons of mix up and budget cuts) and it was thus possible to examine what difference it made.

Where this ad did not play, consumers got their first exposure to the campaign without this mind bridge. They were hit straight out with the ‘You got the right one baby. Uh, huh’ campaign that had only muted reference to taste. The difference in the ads is subtle but the effect in the tracking results was dramatically different. The campaign in those regions never worked anywhere near as well. The problem was that people couldn’t easily ‘cross over’ because the mind bridge to the previous campaigns was missing.

Conclusion.

If you really must change messages, the lesson here is to look for a way to integrate the new message – some way that will reinforce the old at the same time as introducing the new. Construct a mind bridge between the old campaign and the new one that people can use to mentally cross over from one campaign to the other.

That way, the new campaign doesn’t have to ‘wear-in’ or displace the previous campaign and push it out of mind before the new one can catch on. Use a mind bridge to maintain continuity in communications and retain the equity that has built up through investment in all those past campaigns.

Download pdf copy of "Mind Bridges"

Notes

1.The ‘fan effect’ limits how many items can be held in long-term memory. Anderson, J. (2000). Learning and Memory. N.Y., Wiley

2. From Krugman, Dean M., et al ‘Advertising: Its role in modern marketing’ 8th Ed. 1994,Dryden Press, Fort Worth, p364.

.jpg)